On 21 May 2024, the Council of Ministers of the European Union (the "Council") unanimously approved a regulation (the "AI Act") harmonising the rules on artificial intelligence ("AI"). The Council’s position concludes a legislative journey which began on 21 April 2021 with the adoption by the European Commission of a proposal regulation based on article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") and agreement by the European Parliament on 13 March 2024.

Background

Given the increasing significance of AI systems which are rapidly permeating all sectors on a worldwide scale, the intervention of the EU’s lawmakers is certainly necessary. This first attempt at global AI regulation could even be considered as AI-based tools are already integrated into various systems that impact citizens’ daily lives, market operators and consumers. Furthermore, their usage is expected to grow significantly, with ongoing deployment of newer technologies to enhance outcomes and address evolving market needs.

The approach of the AI Act aims to ensure a proper and systematized collection of information, which is essential for an optimal exploitation of AI, while, at the same time, it intends to ensure the highest level of transparency and accountability. Furthermore, governance structures are put in place to guide the transition towards an economy and even a society whereby AI-based systems are closely aligned with the values enshrined in Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union ("TEU"), such as human rights, equality, freedom and democracy as well as the protection of basic assets such as the environment.

Definition of Artificial Intelligence

The framework of the AI Act is based on a very broad definition of artificial intelligence. Accordingly, Article 3 of the AI Act defines the AI as “[…] a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments”.

Following the same logic which underpins definition of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development ("OECD"), this phrasing is as neutral and flexible as possible to avoid the risk of quickly becoming outdated by the rapid evolution of technologies. The main elements of the definition, being (i) operations being led autonomously by AI systems, (ii) adaptiveness and, most of all (iii) the inferring act of generating output from inputs received by the user, appear sufficiently wide to apply to the development of more and more innovative AI systems.

Scope of the AI Act

The AI Act applies principally to AI providers, who are defined as natural or legal (private or public) persons developing and marketing AI systems (or general-purpose AI models), whether for payment or free of charge. Providers need to first assess and document the type of AI systems and the risks associated therewith, as well as make available such information to deployers and users. Other stakeholders subject to the AI Act include product manufacturers, importers, and distributors.

Specific obligations are also imposed on deployers, being developers of AI systems, who may use under their authority, for this purpose, other AI systems, and market these under their own name or trademark. In particular, deployers must take all possible precautions to ensure that they receive all relevant information relating to AI systems from providers (especially when using high-risk AI tools) or otherwise request it.

Similar to most EU internal market legislation, the AI Act has a wide territorial scope. It applies to providers who market AI systems within in the EU, regardless of their location or establishment outside the EU. Deployers of AI systems within the EU are also subject to the AI Act. This includes providers and deployers of AI systems located outside the EU, so long as those systems are used within the EU.

A Risk-based Approach

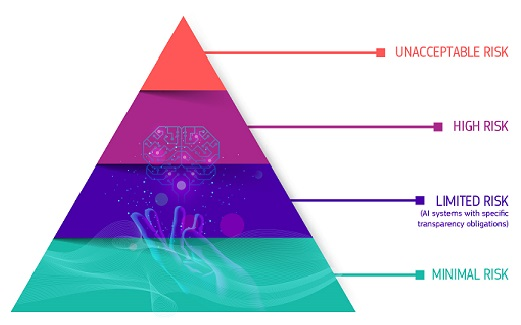

The AI Act advocates an approach to the use of AI systems essentially based on four (4) levels of risk:

[Source: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai]

A Risk-based Approach: AI Systems source of unacceptable risks

Certain AI systems are considered to bear consequences particularly detrimental to the EU values and, as such, the risk inherent in their use is considered unacceptable. Therefore, the marketing of such AI systems is forbidden. The AI Act (Article 5, para. 1, therein) breaks down the list of prohibited AI systems as follows:

- AI systems deploying subliminal, manipulative or deceptive techniques in view of distorting behaviour and prevent informed decision-making, causing significant harm to individuals;

- AI systems exploiting vulnerabilities related to age, disability or socio-economic status in view of distorting behaviour and causing significant harm;

- Biometric categorisation systems inferring sensitive attributes (race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life or sexual orientation), with the exception of the tagging or filtering of lawfully acquired biometric datasets or where law enforcement agencies categorise biometric data;

- “Social scoring” AI systems, allowing the evaluation or classification of individuals or groups based on their social behaviour or personal traits, resulting in a prejudicial or unfavourable treatment;

- AI systems fostering the assessment of the risk of persons committing criminal offences solely based on profiling or personality traits (unless it is used to supplement human assessments based on objective and verifiable facts directly related to criminal activity);

- Facial recognition AI systems allowing the creation of databases by the untargeted extraction of facial images from the internet or from video surveillance images;

- AI systems inferring emotions in workplaces or educational establishments, except for medical or security reasons; and

- AI systems allowing real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible areas for law enforcement purposes, unless where required to (i) search for missing persons, abduction victims, and people who have been human trafficked or sexually exploited, (ii) prevent substantial and imminent threat to life, or foreseeable terrorist attack, or (iii) identify suspects in serious crimes (the AI Act mentions, non-exhaustively: murder, rape, armed robbery, narcotic and illegal weapons trafficking, organised crime, and environmental crime). The exceptional use of AI systems for this purpose is surrounded by safeguards aimed at modulating the often opposing needs for public security and the protection of fundamental rights.

A Risk-based approach: high-risk AI systems

High-risk AI systems involve or may involve a high risk to the health and safety or fundamental rights of individuals. Such systems are not subject to a straightforward prohibition, but their use is subject to compliance with certain mandatory requirements and a conformity assessment.

In accordance with Article 6 of the AI Act, high-risk AI systems can be, respectively, (i) those used as a safety component or a product covered by certain EU laws and required to undergo a third-party conformity assessment under the same laws (such laws being expressly considered in annex I to the AI Act), or (ii) those used in a number of specific cases (as detailed in annex III to the AI Act)[*], a number of exception being provided. [†]

The AI Act imposes specific obligations on providers of high-risk AI systems, as these are required to:

- establish a risk management system throughout the high-risk AI system’s lifecycle;

- conduct data governance, ensuring that training, validation and testing datasets are relevant, sufficiently representative and, to the best extent possible, free of errors and complete according to the intended purpose;

- draw up technical documentation to demonstrate compliance and provide authorities with the information to assess that compliance;

- design their high-risk AI system for record-keeping to enable it to automatically record events relevant for identifying national level risks and substantial modifications throughout the system’s lifecycle;

- provide instructions for use to downstream deployers to enable the latter’s compliance;

- design their high-risk AI system to allow deployers to implement human oversight;

- design their high-risk AI system to achieve appropriate levels of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity; and

- establish a quality management system to ensure compliance.

A risk-based approach: limited- and minimal-risk AI systems

In contrast with AI systems bearing unacceptable- and high-risk, AI systems involving limited or minimal risk are generally considered as lawful and only required to comply with certain minimum transparency requirements.

Several AI systems are considered of limited risks under the AI Act, such as those for emotion recognition and biometric categorisation systems, chatbots and several kinds of content generation. Such AI systems are mainly subject to disclosure requirements, as providers and deployers need to provide individuals with all the relevant information (subject to limited exemptions).

Other systems, such as videogames and spam filters integrating AI, are considered to pose minimal risks and as such are not subject to mandatory requirements. Nevertheless, providers are encouraged to voluntarily adhere to specific codes of conduct.

Provision of AI general purpose models and systems

Under the AI Act, general-purpose AI ("GPAI") models are refined as models displaying significant generality and competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks, then integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications (the definition does not cover AI models used for research, development, or prototyping activities before their placement on the market). GPAI systems are AI systems based on such GPAI models and have the capability to serve a variety of purposes, both for direct use as well as for integration in other AI systems.

Given GPAI systems can be used as such or integrated into high-risk AI systems, providers of GPAI models are subject to strict obligations, mainly aimed at producing a body of technical documentation allowing information, training, testing and evaluating the results, smoothing the integration of the AI model into further AI systems and respecting the EU rules on copyright and intellectual property.

Specific rules are provided for GPAI models when these present systemic risks, as providers are under a notification obligation to the European Commission, which assesses (possibly requesting the advice of a qualified alert from the scientific panel of independent experts) whether a GPAI model has systemic implications. Furthermore, providers of GPAI models implying systemic risks are also required to track, document and report possible incidents to the Artificial Intelligence Office (the "AI Office") and national competent authorities, take action to mitigate systemic risks and ensure an adequate level of cybersecurity protection.

Importantly, following the logics of internal market and mutual recognition, GPAI model providers may demonstrate compliance with their obligations if they voluntarily adhere to a code of practice. Once harmonised standards are published, compliance with these will lead to a presumption of conformity.

Governance matters

The complexity of the AI Act prompted the EU lawmaker to establish specific governance bodies. As such, the AI Office, established at European level, has the task of supervising the implementation and enforcement of the AI Act. In particular, the European Commission shall entrust its competences to enforce the provisions on GPAI models to the AI Office (for instance as to the evaluation of GPAI models).

As in the case of other agencies established at the EU level, the AI Office shall assist national competent authorities, in particular regarding market surveillance of high-risk AI systems. As predicted, the office shall assist AI providers in drafting codes of conduct, which should foster their compliance with the relevant standards under the AI Act.

Besides the AI Office, an Artificial Intelligence Board, composed of representatives of EU member states will assume a steering function by providing soft law advice, opinions and recommendations.

Sanctions

Article 99 of the AI Act provides for penalties, articulated, in conformity with the principle of proportionality, on the seriousness of the breach and the size and turnover of the author. Therefore, both the type and intensity of the sanction are variable, with orders, warnings and fines being applicable, based on several criteria. Among the most significant penalties, the following can be considered:

- failure to comply with the prohibition on AI systems may be sanctioned with fines up to EUR 35m or 7% (seven percent) of the total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is greater;

- a breach of certain provisions relating to high-risk AI systems may result in a fine up to EUR 15m or 3% (three percent) of the total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is greater; and

- the provision of incorrect, incomplete or misleading information to competent authorities may also result in a fine of up to EUR 7.5 m or 1% (one percent) of total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is greater.

Entry into force

The AI Act is expected to be published in the Official Journal of the European Union in July 2024 and, in accordance with the TFEU’s rules, will enter into force 20 (twenty) days following its publication and should become applicable 24 (twenty-four) months as of the date of entry into force.

Nevertheless, the act establishes certain specific timelines for the applicability of its provisions, as the provisions:

- on prohibited AI systems shall be applicable 6 (six) months after the entry into force of the AI Act,

- on GPAI shall be applicable 12 (twelve) months thereafter,

- on high-risk AI systems (under annex III) shall be applicable 24 (twenty-four) months thereafter, and

- high risk AI systems (under annex I) shall be applicable 36 (thirty-six) months thereafter.

The way forward

An analysis of the provisions of the AI Act reveals how, in this first attempt to create a comprehensive regulation for AI, the EU lawmakers tried to strike a very delicate balance. They sought to establish necessary limits on the use of intrusive technologies whilst also enhancing basic public policies such as public security and public order.

This issue is particularly evident as the AI Act establishes exceptions, even for the use of unacceptable AI systems, notwithstanding their potential impact on fundamental rights. Given that the legislative provisions required extremely nuanced case-by case implementation, it is difficult to predict whether the safeguards outlined in the AI Act might hinder efficient utilisations of AI systems in the security area or inadvertently intrude upon individuals’ private lives. Article 2 of the TEU underscores the principle that security should transform into repression, reminiscent of a chilling Minority Report scenario.

The three-year long legislative process itself, though not uncommon in other, potentially less impactful areas of the internal market, vividly illustrates this dilemma, as the initial proposal from the European Commission underwent significant amendments (largely by the European Parliament). As the EU strives to set the benchmark for AI, mainly addressing US-resident providers, its stands at the forefront of this modern retelling of the eternal conflict between freedom and authority.

[*] Such as AI systems relating to biometrics not causing unacceptable risks, critical infrastructure, education and vocational training, employment, access to essential public or private services, law enforcement, management of migration, asylum and border control and administration of justice and democratic processes.

[†] I.e., except if the AI system (x) performs a narrow procedural task; (y) improves the result of a previously completed human activity; (z) detects decision-making patterns or deviations from prior decision-making patterns and is not meant to replace or influence the previously completed human assessment without proper human review; or (t) performs a preparatory task to an assessment relevant for the purpose of such cases (as listed in annex III to the AI Act).

Share on